How AI Is Going to Affect Architectural Photography

The Evolution of Telling Timeless, Elegant Stories

I began my career 35 years ago torn between completing my registration as an architect or following my heart into photography. After school, feeling disillusioned, I took a job helping a photographer document all of Richard Meier’s residential projects for a book. The experience hooked me instantly.

A photographer’s—at least my—deepest desire has always been to tell a timeless, elegant story of your work. And as the tools have evolved, so has the way that story can be told. Architectural photography has never been static; it has grown through eras of long exposures, toxic chemistry, large-format film, digital sensors, and now artificial intelligence. Each shift has changed how we see architecture, interpret it, and communicate its meaning. Photography began as documentation. It grew into interpretation. Then it became storytelling. And now, with AI, it is becoming a collaboration between intention and possibility.

From Mechanical Perspective to Photographic Vision

Albrecht Durer | The Triumphal Arch, 1515 | Woodcut Print

Nicephore Niepce | French Commune in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, 1826 | Heliograph

The desire to translate three dimensions onto a flat surface reaches back to Albrecht Dürer’s perspective machine in 1510. When Nicéphore Niépce created the first photograph in 1826, that same pursuit—capturing reality faithfully—took a massive leap.

What’s remarkable is that even today, through digital sensors and AI tools that predict light instead of simply recording it, the core goal hasn’t changed: to merge reality and imagination into one frame and to express what the architect meant for people to feel. This is why conversations about AI matter. AI isn’t arriving into emptiness; it’s entering a craft defined by discipline, patience, interpretation, and an obsession with clarity.

When Architectural Photography Was Pure Documentation

Eugene Atget - The Pantheon, 1924

In the early 20th century, photographers like Eugène Atget walked Paris like archaeologists. With a large-format camera, he made frontal, systematic images of storefronts, staircases, and quiet corners of the city. His message was simple:

“Here it is.”

“We built this.”

The exposures were long.

The equipment was heavy.

And the process was expensive.

Yet these images formed a cultural record that shaped how architecture would be documented for decades.

The Bauhaus, Modernism, and the Birth of Interpretation

Mile Van der Rohe & Lilly Reich - Barcelona Pavillion 1929

By the 1920s and 30s, the Bauhaus began reshaping not only how buildings were designed but how they were meant to be seen. Architecture shifted from brick and mortar to steel and glass, from mass to transparency. Photography followed.

In the 1940s, as film became more reliable—now even in color—the relationship between architects and photographers strengthened. Publication became essential for success, and photography became part of the architectural conversation rather than something that happened after the fact.

The Photographers Who Defined an Era

Julius Shulman - Case Study House #22 (Stahl House) Copyright Julius Shulman

This era ushered in giants: Ezra Stoller on the East Coast, Julius Shulman on the West, and Hedrich-Blessing in Chicago. They introduced drama through angle, lighting, and atmosphere. Photography stepped beyond documentation and into interpretation.

Gensler | Warburg Pincus Lake Offices | Interior Design | Award Society of American Register Architects (SARA) Award of Honor | Photographer David Joseph

Ritual and Restraint of Shooting Film

Alice Cha Residence, Hamptons NY | Published in Interior Design Magazine | Photographer David Joseph

Film photography demanded patience and mastery. Clear skies by day and the perfect blue hour by night were priceless. Photographers were generalists, often taking whichever assignments kept their businesses afloat. Even Ansel Adams photographed architecture when commissioned. But the best photographers—those who truly saw—could express light, proportion, material, and atmosphere in a way that transcended mere recording. Shooting film felt like attending church in the old Latin mass: ritualistic, mysterious, and full of hope that the final image would emerge from the developer properly exposed and in focus.

Yet film came with a cost:

It was toxic and harsh on the environment.

It was unforgiving.

It was expensive—I spent about $40,000 a year on film and Polaroid in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Every click mattered.

Every exposure was a lesson.

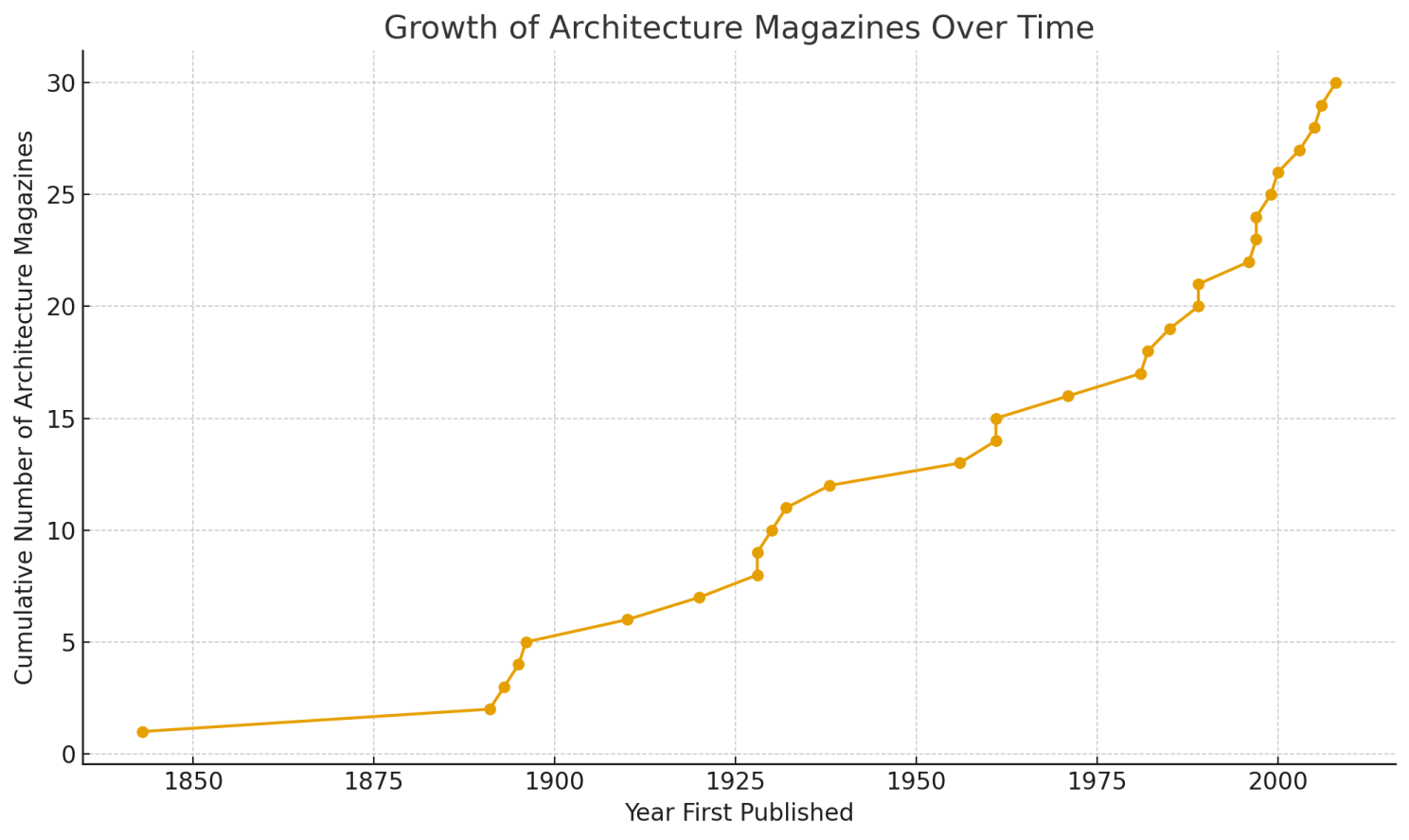

David Joseph AIA Maine Annual Conference Talk | Growth of Architecture Magazines Over Time

When Digital Changed Everything

By the 1980s and 90s, architectural magazines exploded in influence, speeding up the demand for polished, publication-ready imagery. Then digital photography arrived and completely transformed the workflow.

Film’s beauty was undeniable, but its limitations—especially around reflections, color accuracy, and architectural precision—often prevented us from fully expressing an architect’s intention.

The first digital backs cost around $60,000—a second mortgage disguised as a camera. But the advantages were enormous:

No chemicals

No darkroom

Instant review

The freedom to experiment, adjust, or fail safely

The ability to shoot significantly more frames in a day

David Rockwell Design | JFK Terminal | Interior Design | Digital Composite | Photographer David Joseph

Digital democratized photography, lowering barriers for newcomers. Yet despite this easier entry, large firms kept investing in photographic mastery. High-level craft still attracted high-level clients. Pritzker-winning architects needed images that communicated clarity, intention, and emotion—photographs capable of telling a story.

Digital also elevated retouching into an artform. We could finally control reality inside the image: layer exposures, balance light inside and out, remove distractions, and grade color to perfection.

The tools improved, but the artistic eye still determined whether the result felt believable, intentional, and alive.

The Limits of Digital—and the Promise of AI

Even with digital’s flexibility, some things remained difficult or impossible: adding people convincingly, changing time of day, altering reflections, adjusting materials, or reimagining architectural elements while maintaining realism. Only a small group of specialists could push these boundaries while keeping an image emotionally authentic.

AI is the next major leap in innovation, but it isn’t replacing architects or photographers. Instead, it accelerates workflows and expands what’s possible:

Changing seasons

Adjusting light

Removing or adding distractions

Recoloring or restyling materials

Adding people, foliage, vehicles

Refining architectural lines

Tasks that once took days now take seconds.

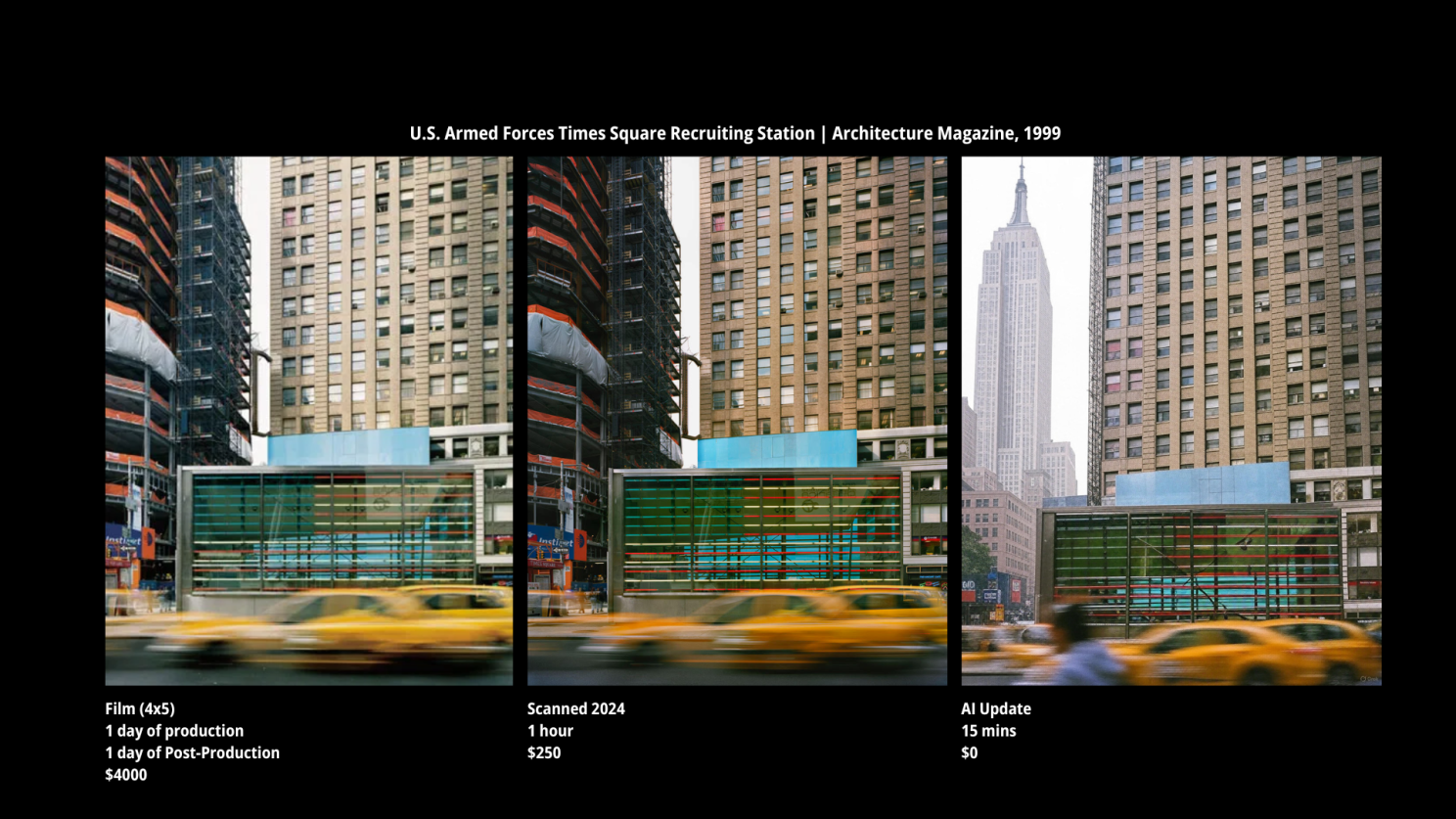

Comparison of Film, Digital Retouch and AI

But speed introduces a new challenge: AI makes interpretive decisions without context or consent. For example, when I asked AI to enhance a 1999 image of the U.S. Armed Forces Times Square Recruiting Station, it added people who weren’t there, changed colors, altered taxis, and modified textures—choices that weren’t mine or the architect’s.

Vocon | The Quarter II | LEED Homes Silver | Photographer David Joseph

Likewise, a 2021 project required a retoucher to manually correct the positions of 600 window shades—a 25-hour, $600 task. Retoucher Thomas Seely recreated the correction using Generative AI, it took one hour and cost $300.

As he described by Retoucher Thomas Seely:

“Generative fill speeds up retouching, but it still needs manual refinement and struggles with high-resolution files. We’re in a honeymoon phase right now AI tools are cheap and powerful—but Adobe will eventually charge more.”

The craft hasn’t been replaced—it has been redirected. We’ve traded toxic chemistry for toxic computing, but the need for a discerning human hand remains.

What AI Won’t Change

Gensler | Silver Lake - Hudson Yards | Photographer David Joseph

After everything—film, digital, retouching, AI—the heart of architectural photography remains the same. AI will become another essential tool, just like digital sensors, Photoshop, and VR walkthroughs. It may retire certain equipment (Canon has already discontinued the tilt-shift lens I used on some projects), but it won’t retire the craft. Instead, AI will broaden access: smaller firms will gain exposure they’ve never had, and young architects can present work with a polish once reserved for large teams. Yet simultaneously, larger firms will rely on their photographers more than ever. Why? Because architectural photography has never been merely documentation.

It is a partnership.

It is light, space, proportion, intention.

It is the act of translating something massive and deeply considered into an experience someone can feel in a single frame.

And regardless of how the tools evolve, the goal endures: to make a building’s purpose clear, to show its impact on the people who use it, to reveal the idea behind the design, and to remind people that architecture—like photography—begins with wonder.